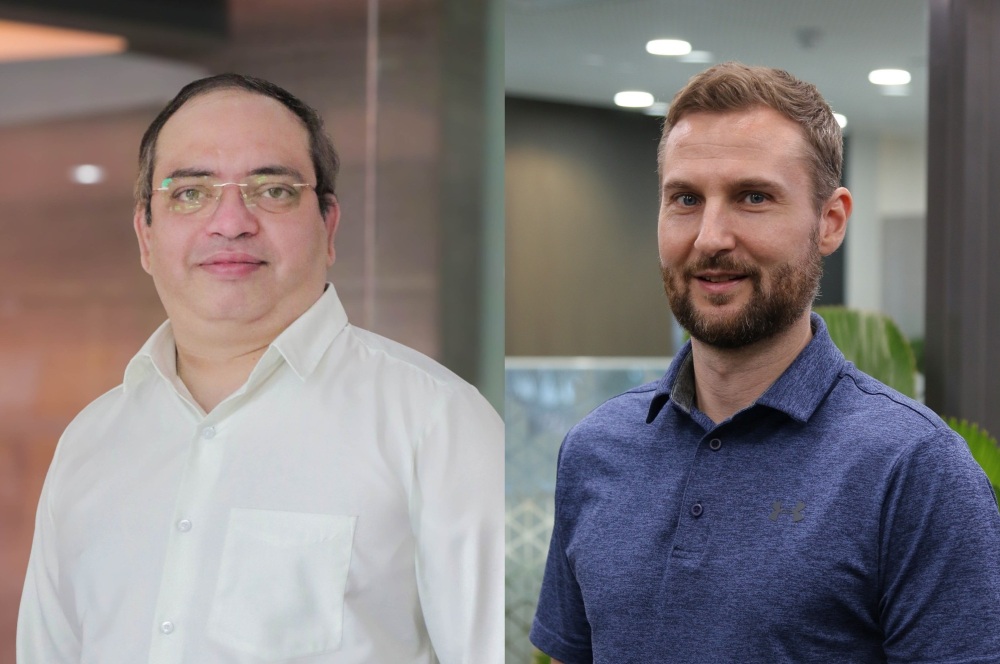

Navigating Vietnam’s new Law on Artificial Intelligence

Vietnam’s first-ever Law on Artificial Intelligence (AI) was passed on 10 December 2025 and will take effect from 1 March 2026, marking a milestone in the country’s digital governance and innovation strategy.

Plugging nuclear energy safely into Vietnam’s grid

Vietnam’s new Atomic Energy Law opens the door to advanced nuclear technologies, but success will hinge on grid readiness, safety culture, and skilled people, say RMIT University Vietnam academics.

RMIT experts flag security and mental health risks from unverified content

Experts in information technology, psychology and communication from RMIT Vietnam share their perspectives on the risks associated with consuming and spreading unverified information online.

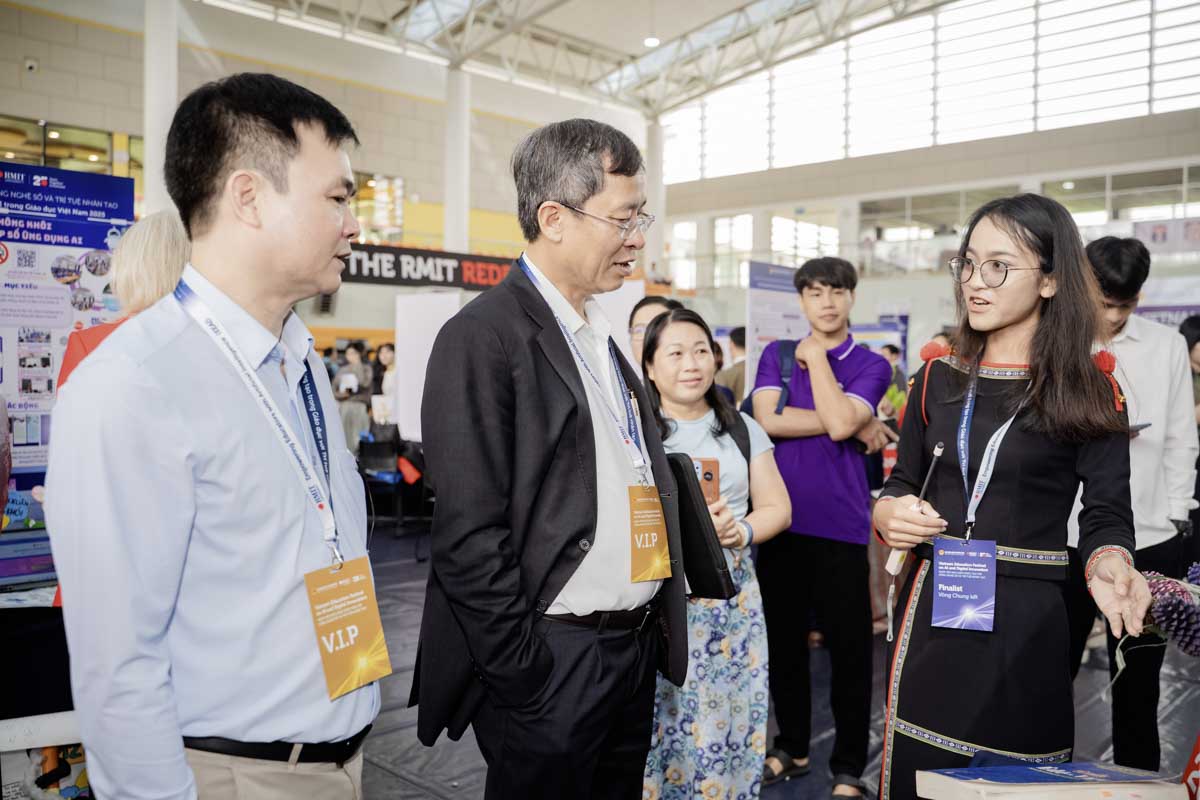

Vietnam Education Festival honours AI innovations in education

Co-organised by the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) and RMIT Vietnam, the Vietnam Education Festival on AI and Digital Innovation 2025 created a nationwide platform for teachers to connect, learn and share best practice.