Despite the obstacles, momentum is building. A national steering committee led by the Prime Minister and a strategic plan to train 50,000 semiconductor engineers by 2030 signal high-level commitment. “We are entering a critical phase,” Dr Minh said. “With the right moves now, Vietnam can become a serious player in Southeast Asia’s semiconductor race.”

Designing Vietnam’s technology power by 2050

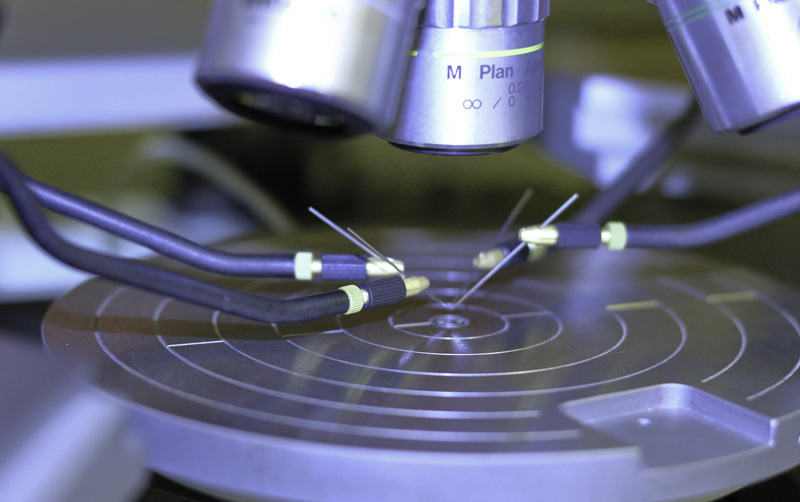

The semiconductor industry serves as the driving force of modern technological progress, fostering innovation across artificial intelligence (AI), internet of thing (IoT), edge and cloud computing, telecommunications, automotive, and consumer electronics.

Vietnam’s opportunity lies in supply chain diversification. As geopolitical tensions push companies to seek alternatives to China and Taiwan, the country stands to benefit. “We’re seeing more research and development investment, not just assembly,” Dr Minh said. Firms like Synopsys and Faraday are ramping up research efforts in fields ranging from medical devices to data centres.

Several frontier technologies are also on the radar. In-memory computing, which could dramatically reduce energy consumption for AI hardware, and quantum chip development for fields like cryptography and pharmaceuticals, are among them.

“AI-driven chip design tools from companies like Cadence and Siemens are also redefining how fast and cost-effectively chips can be made,” he added.

Still, transformation won’t be automatic. “This is a high-stakes game,” he warned. “Without real investment in talent, infrastructure, and IP protection, we risk missing the window.”

To succeed, Dr Minh believed Vietnam must take a systems-level approach. “It’s not enough to train engineers. We need a coordinated strategy where government, industry, and universities work together.”

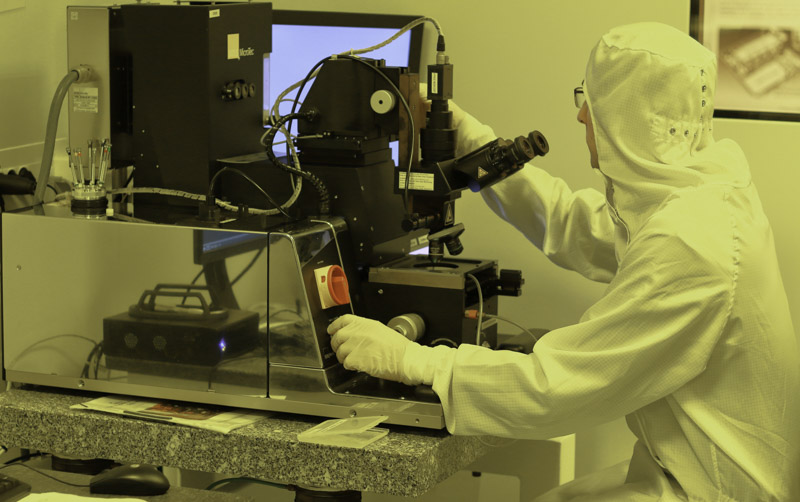

Assembling Vietnam’s semiconductor future

Government must lead on incentives and infrastructure. “Beyond tax breaks, subsidies, and grants to attract semiconductor fabrication and R&D investments, we need to invest in a national semiconductor fabrication foundry and enhance the reliability of electricity, water supply, and logistics infrastructure to support high-tech semiconductor research and development activities and manufacturing,” Dr Minh said. Legal frameworks for intellectual property protection and technology transfer agreements with leading global companies like TSMC or GlobalFoundries are equally critical.

Businesses also have a central role to play, especially local companies. “Promoting partnerships between local enterprises, such as Viettel and FPT, and global semiconductor leaders, including Intel, Samsung, Cadence, Synopsys, TSMC, is essential for enabling knowledge transfer and driving technological advancement,” Dr Minh suggested.

Education is perhaps the key player. “We need to embed chip design, microelectronics, and semiconductor physics into our curricula,” Dr Minh said. “But more than that, we need strong ties between academia and industry to create job-ready graduates.”

RMIT Vietnam is well-positioned to support the country’s semiconductor transformation through education, industry collaboration, and knowledge exchange. “By offering specialised academic programs, fostering partnerships with global and local semiconductor leaders, and hosting knowledge-sharing events, we can play a pioneering role in developing Vietnam’s high-tech talent and innovation ecosystem.”