Vietnam’s electronics industry has emerged as a standout success in attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). Multinational electronics corporations, such as Samsung, Intel, and LG, consistently rank among the top investors in Vietnam. Together, FDI firms account for around 98% of the country’s electronics exports, which reached US$126.5 billion – or a third of all total export revenues – in 2024. This is clear evidence of the role that electronics FDI plays in Vietnam’s manufacturing sector and the wider economy.

The prevailing narrative is that FDI fuels technology transfer, boosting domestic firms’ managerial capabilities, technology, and productivity. However, recent research conducted by Economics lecturer Dr Nguyen Chau Trinh and his colleagues at RMIT University Vietnam shows a persistent technology gap between domestic firms and intra-industry FDI firms, signalling limited technology spillovers.

“A dominant FDI presence in the value chain would further intensify competition, crowding out domestic firms or confining them to low-value-added segments with limited opportunities for technological upgrading,” warned Dr Trinh.

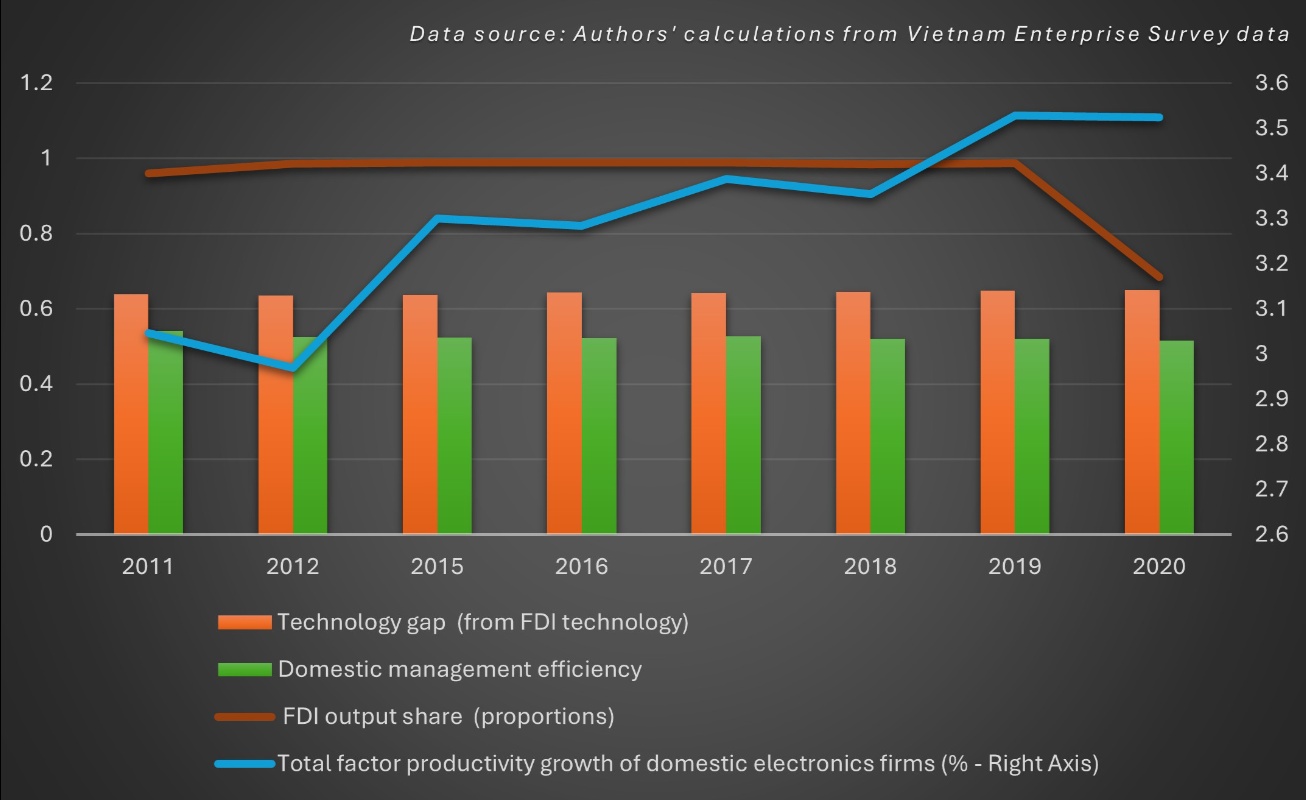

Findings from the study, which is based on the Vietnam Enterprise Survey data published by the General Statistics Office and advanced technology and productivity analysis techniques, show that domestic firms have made some gains in management capabilities by observing the practices of FDI giants – a positive example of the so-called "demonstration effect". However, technological upgrading remains elusive. On average, domestic firms operate at only 64% of the technological frontier defined by FDI firms – and this gap has not narrowed in a decade, from 2011 to 2020.

Management efficiency and technology ratio evolvement in Vietnam’s electronics industry

Management efficiency and technology ratio evolvement in Vietnam’s electronics industry

“Our findings reveal an asymmetry between managerial and technological spillovers: FDI providers and customers rarely provide both,” research co-author Associate Professor Pham Thi Thu Tra noted.

A key reason provided by the researchers is the structure of global value chains in electronics. In producer-driven industries like electronics, core technologies and designs are tightly controlled by lead firms headquartered abroad. Without joint ventures or mandated linkages, traditional technology spillovers through partnerships or supplier relationships are weak.

“However, even when technology transfer is limited, FDI management practices, being visible and non-proprietary, can spill over to local firms, raising industry standards and driving productivity gains,” RMIT Senior Program Manager of Economics Dr Ha Thi Cam Van said.

Findings from the RMIT research reveal that the impacts of FDI are not uniform:

Korean and Japanese FDI, which dominate Vietnam’s electronics sector, tend to operate closed networks, bringing their own suppliers and limiting local linkages.

ASEAN and Chinese investors, by contrast, show more inclusive practices in some segments, leading to modest gains in management and technology among Vietnamese firms.

The effects also vary across value chain positions:

Upstream FDI in metal components supports domestic productivity through better-quality inputs.

Downstream FDI in industries such as plastics forces domestic firms to upgrade technologically but often under intense competitive pressure that undermines management efficiency.

However, the researchers also found that gains in total factor productivity (total contribution of technology and efficiency in inputs used in producing output) among domestic electronics firms are driven more by their own efforts, such as innovation and human capital development, than by external spillovers from FDI.

The electronics industry plays an important role in Vietnam’s economy.

The electronics industry plays an important role in Vietnam’s economy.

The findings have important policy implications. While FDI has powered Vietnam’s export-led growth in electronics, simply increasing FDI inflows may no longer suffice. Without targeted interventions, the “more is actually less” phenomenon, where rising FDI presence correlates with limited domestic upgrading, could entrench Vietnam’s role as an assembly hub rather than a centre of innovation.

To avoid this trap, the researchers recommend that Vietnam:

Promote deeper domestic-foreign linkages, through incentives for local sourcing and supplier upgrading.

Encourage joint R&D and co-development projects, especially with ASEAN and Chinese partners who exhibit more inclusive sourcing behaviours.

Strengthen domestic capabilities in technology and innovation, so local firms can compete in higher-value segments.

Prioritise learning and diffusion policies, not just FDI attraction.

As Vietnam targets high-tech growth in its next phase of industrialisation, the challenge will be to ensure that FDI drives not just exports but meaningful domestic upgrading.

“Policy interventions mandating certain domestication thresholds could prove instrumental in fostering and strengthening connections between FDI enterprises and local businesses,” says Dr Dao Le Trang Anh, one of the study's authors.

Explore more findings from the study in the A*-ranked Research Policy journal.

Thumbnail image: niyazz – stock.adobe.com | Masthead image: IM Imagery – stock.adobe.com

The explosive growth of affiliate marketing across social media and e-commerce platforms is exposing significant legal and ethical risks, according to experts from RMIT Vietnam.

Under the MoU, both parties will collaborate to enhance Vietnam’s enterprise competitiveness and national branding efforts in domestic and international markets.

Hidden costs in the supply chain could price some Vietnamese exporters out of Europe.

A UN Women-RMIT partnership is helping advance leadership capability and support Vietnam’s SME development agenda.