Studies have shown that these microplastics can infiltrate aquaculture systems through contaminated water, feed, and even plastic materials used in farming infrastructure like nets and containers. Fishmeal and shrimp feed have already been flagged as potential carriers. This means that even the most carefully managed aquaculture farms may not be immune.

What can technology do?

Innovations in food technology offer hope. Globally, solutions like advanced filtration, adsorption, magnetic removal, and biodegradation techniques are being explored, though many face cost and implementation hurdles.

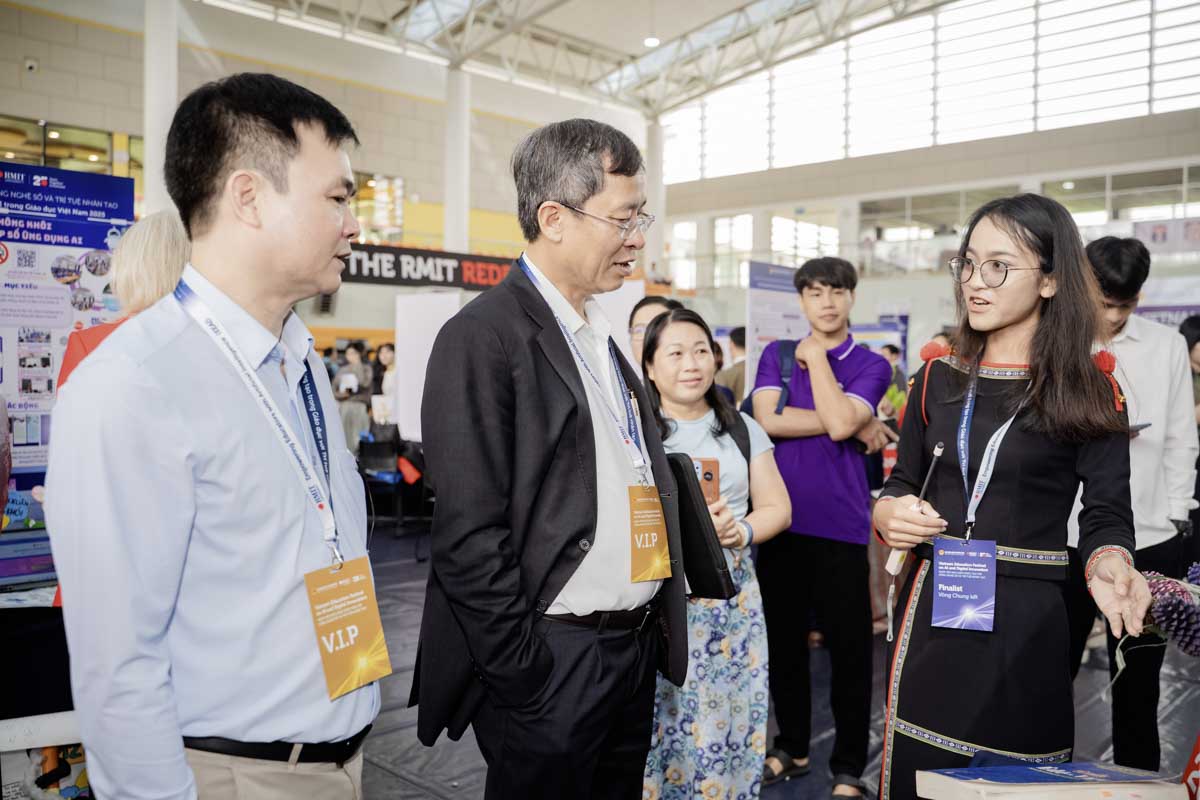

At RMIT Vietnam, researchers from the School of Science, Engineering & Technology are planning on using AI technology to detect microplastics on the surface of fish. If successful, this could become a valuable tool for quality control and contamination reduction in seafood supply chains. More local research and investment are needed to assess how scalable and affordable such solutions might be across Vietnam’s diverse aquaculture sector.

What can consumers do?

This is where the waters get murky. Unlike nutrition or antibiotic use, microplastic contamination is nearly invisible to consumers, and current labelling systems do not account for it. While some suggest greater transparency in sourcing and feed composition, others argue that the science is still catching up.

In Vietnam, researchers have found high concentrations of microplastics in lakes, canals, and urban areas such as Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi. So, for now, consumers can reduce their own plastic footprint – opting for reusable containers, avoiding microwaving in plastics, and supporting brands that adopt sustainable practices.

In the long term, prevention is key. Reducing plastic waste at the source, investing in biodegradable materials, and cleaning up waterways must become national priorities. For Vietnam, aligning aquaculture policy with environmental reform could yield both economic and public health benefits.

With strategic collaboration between researchers, regulators, industry, and the public, Vietnam can take meaningful steps to protect its reputation as a fishery powerhouse, and more importantly, safeguard the health of its people and ecosystems.

Story: Dr Yunus Khatri, senior lecturer in Food Technology and Nutrition, School of Science, Engineering & Technology, RMIT University Vietnam

Thumbnail image: SIV Stock Studio – stock.adobe.com