“I remember the beginning of vision and object identification. During my second research post we were working at an air traffic control centre in France, where they were using these expert decision systems, that at the time, were just demonstrators and prototypes. It was all old school AI.”

The area that Dr. Porteous originally worked in was called Automated Planning, which is thinking about tasks that need to be done and the order in which they must be completed. This created an early AI general problem solver. “Whatever the problem is, if I can encode it using this representation of action and change, then I can solve it.” Dr. Porteous explains. “That was the dream then, and in a way, it persists today. A lot of highly difficult questions from those first days of AI, such as genuine understanding, genuine general strategies that can be applied in new situations and creativity and design, we still deal with now.”

Society is also dealing with the repercussions of AI, specifically regarding certain professions, that are said to be under threat due to the power of AI tools. Dr. Porteous confides, however, that many of these jobs will more than likely just be changed so that the human focus will be shifted to more important details. AI will help filter out the tasks that humans won’t need to deal with anymore.

“The genie is already out of the bottle,” Dr Porteous notes. “These are computer systems and tools that we use already. The real question is how we use them and how we interact with them.”

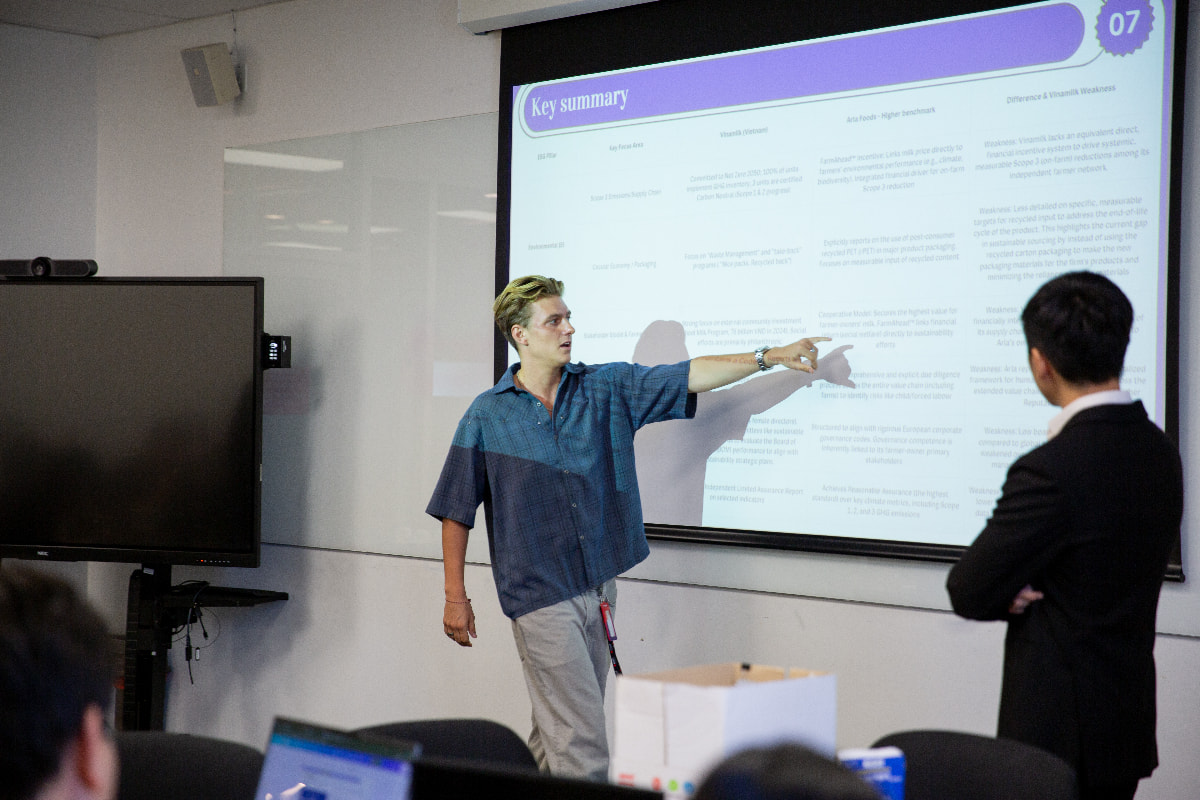

The question of ethics in AI is one that RMIT takes seriously, and it is a part of the master’s program developed by Dr. Porteous. “There needs to be an element of social responsibility in the system. As developers, we must ask is it functional? Is it legal? Is it fair and nonbiased? Our international communities, of which RMIT is a part of, are focused on using AI to work for societal good, such as anti-poaching in Africa, on medical research or on progressing human wellbeing and mental health.”