Is gold worth considering amidst Vietnam’s dynamic market landscape?

RMIT Finance Lecturer Dr Dao Le Trang Anh reflected on the recent surge in domestic gold prices and provided analysis on investment options in the current market.

Vietnamese companies can elevate their brands by focusing on core values

How important is branding through value-adding for Vietnamese firms' international success? RMIT University researchers shared some insights as part of Vietnam National Branding Week 2024.

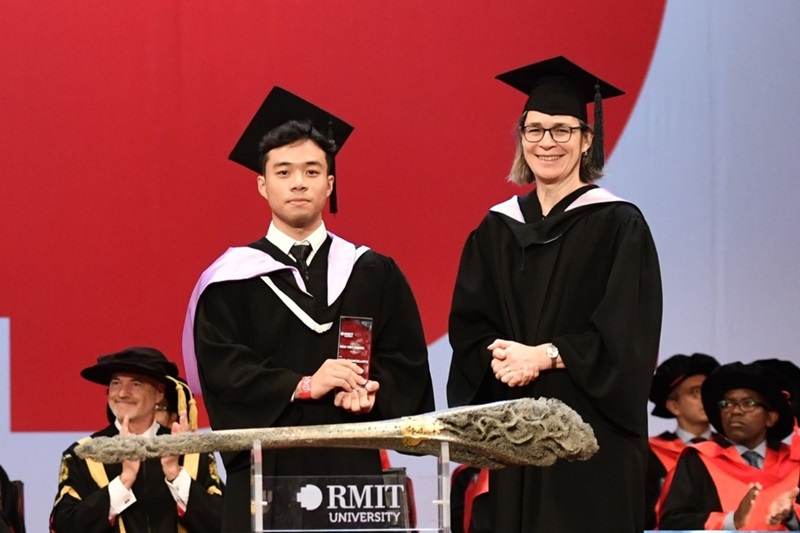

Top graduate of RMIT Class of 2024 found success through perseverance

The university journey of fresh RMIT graduate Ngo Viet Luong is one marked by resilience and a growth mindset.

Digital literacy skill enhancement for women entrepreneurs

If digitally trained, women who make up the majority of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) could hold the potential to accelerate national economic growth, according to RMIT Vietnam researchers.